Overview of Polygon zkEVM: How the Layer 2 solution for Ethereum works

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) scaling solution, specifically the Layer 2 blockchain, Polygon zkEVM. How does this blockchain address the high gas fees in transactions while leveraging the other benefits of ZK-Rollups? You’ll find the answers to these and other questions in this article.For a more detailed understanding of Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP), we recommend checking out this article in our Blockchain Wiki on GitHub.Introduction

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) scaling solution, specifically the Layer 2 blockchain, Polygon zkEVM. How does this blockchain address the high gas fees in transactions while leveraging the other benefits of ZK-Rollups? You’ll find the answers to these and other questions in this article.For a more detailed understanding of Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP), we recommend checking out this article in our Blockchain Wiki on GitHub.IntroductionPolygon zkEVM is a second-layer blockchain for Ethereum, a scaling solution that utilizes zero-knowledge (ZK) proofs. It employs a cryptographic primitive known as a ZK proof to verify state transitions. By combining data availability and execution verification at the Ethereum L1 level, it ensures the security and reliability of L2 state transitions.

zkEVM enables developers to deploy Ethereum smart contracts on L2 without any code modifications, benefiting from the advantages of ZK-Rollups such as low gas costs and fast transaction finalization.

A zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) is a method in cryptography that allows one party (the prover) to prove to another party (the verifier) that a statement is true, without revealing any information other than the fact of the statement’s truth. This method has found extensive application in cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies as it enables transactions or actions that guarantee a high level of privacy and security.

Blockchain Efficiency Strategy- The first strategy involves deploying a consensus contract that incentivizes the most efficient aggregators to participate in proof generation.

- The second strategy is to perform all computations off-chain, storing only the necessary data and zk-proofs in the blockchain.

- Implementation of a bridge smart contract, for example, using the UTXO method.

- Use of specialized cryptographic primitives in zkProver to accelerate calculations and minimize proof sizes, applicable through:

- Launching a specialized zero-knowledge assembly language (zkASM) for bytecode interpretation.

- Utilizing zero-knowledge tools such as zk-STARK for proof purposes; these proofs are very fast, though larger in size.

- Instead of publishing large zk-STARK proofs as authenticity proofs, zk-SNARK is used to verify the correctness of zk-STARK proofs. These zk-SNARKs, in turn, are published as proof of state changes. This helps reduce gas costs from 5 million to 350 thousand.

To understand how the protocol works, one needs to know about state management and the transaction lifecycle.

State ManagementIt is important to explain how the Polygon zkEVM protocol manages L2 Rollup states while ensuring data verifiability and secure state transitions.

To begin, some definitions:

- Sequencer is a node (zkNode) responsible for selecting transactions from the pool database, verifying transaction authenticity, and subsequently placing valid ones in a batch;

- Aggregator is a similar node (zkNode), configured to provide proofs that validate the integrity of the state change proposed by the sequencer. These proofs are zero-knowledge proofs (or ZK-proofs), and for this purpose, the aggregator uses a cryptographic component called Prover;

- Prover is a sophisticated cryptographic tool capable of creating hundreds of ZK-proof packets and combining them into one ZK-proof, which is published as proof of authenticity;

- PolygonZkEVM.sol is an L1 smart contract that checks the validity proofs to ensure the correct execution of each state transition. It achieves this using zk-SNARK schemes. It receives batched transaction sequences from sequencers, stores their order, verifies the transactions, and posts them in L1.

The trusted sequencer generates batches of transactions, but to achieve rapid finality of L2 transactions and avoid waiting for the next L1 block, they are transmitted to L2 network nodes through a broadcasting channel. Each node will execute the batches to locally compute the resulting L2 state.

Once the trusted sequencer records the sequence batches received directly from L1, the L2 network nodes will re-execute them, and they no longer have to trust it.

The off-chain executed batches will ultimately be verified on the blockchain using Zero-Knowledge Proof, after which the resulting L2 state root will be recorded.

As the zkEVM protocol evolves, L2 network nodes will directly receive state updates from L1 nodes. Blockchain state data will be transmitted and updated between the two network levels, improving communication and synchronization between them.

This means that both data availability and transaction execution verification entirely depend on the security assumptions of the first level (L1). In the final stage of the protocol, nodes will rely solely on the data present in L1 to maintain synchronization with each L2 state transition. This underscores the importance and reliability of L1 in ensuring the security and integrity of the entire system.

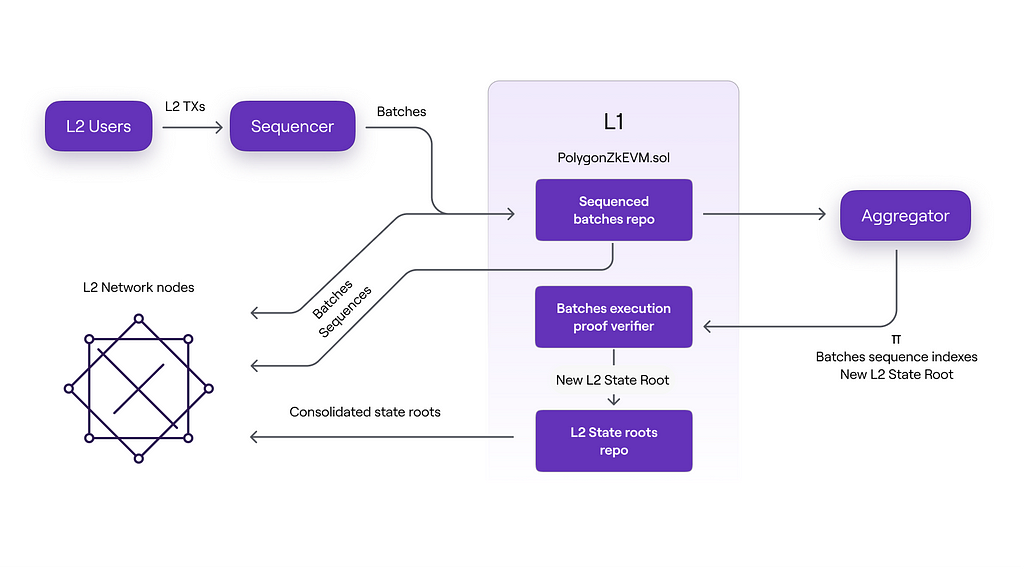

The diagram below shows how L2 nodes receive transaction packets.

- Directly from the trusted sequencer before the packets are transmitted to L1, or

- Directly from L1 after sequencing batches or

- Only after the correctness of execution is proven by the Aggregator and verified by the PolygonZkEVM.sol contract.

It should be noted that the three packet data formats are accepted by L2 nodes in the chronological order listed above.

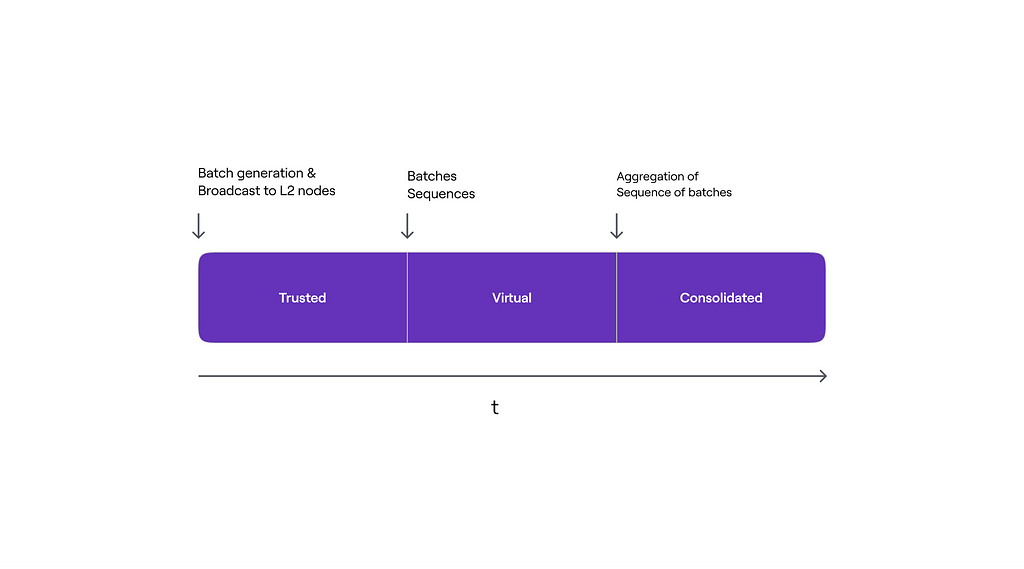

Thus, there are three stages of the L2 state, each corresponding to three different ways of state updating by L2 nodes:

- Trusted State: in the first stage, updates are based solely on information (i.e., packets consisting of ordered transactions) received directly from the trusted sequencer before the data becomes available in L1;

- Virtual State: in the second stage, updates are based on information received from the L1 network by L2 nodes. This happens after the packets have been sequenced (ordered) and data has become available in L1;

- Consolidated State: in the final stage, the information used to update the L2 state includes verified zero-knowledge proofs of computational integrity. That is, after the zero-knowledge proof has been successfully verified in L1, L2 nodes synchronize their local L2 state root with the one recorded in L1 by the trusted Aggregator.

The image below illustrates the timeline of L2 state stages in terms of packet processing, as well as the actions that trigger the transition from one stage to another.

Transaction Lifecycle

Transaction LifecycleThis section details the various forms and stages that L2 user transactions undergo, from their creation in user wallets to their final verification by irrefutable proofs on L1.

Sending TransactionsTransactions in the Polygon zkEVM network are created in users’ wallets and signed with their private keys.

After creation and signing, transactions are sent to the Trusted Sequencer node via the JSON-RPC interface. The transactions are then stored in a pending transaction pool, where they await the Sequencer’s decision to execute or reject them.

Users and zkEVM communicate using JSON-RPC, which is fully compatible with Ethereum RPC. This approach allows any EVM-compatible application, such as wallet software, to function and feel like true Ethereum network users.

Important! It should be noted that in the current design of zkEVM, one transaction is equivalent to one block.

How can this improve blockchain operation?

- Simplifying Communication: Typically, in blockchains, multiple transactions are grouped into blocks. But in this case, each transaction itself forms a block. This can simplify the data transfer process between network nodes.

- Compatibility with Tools: Since each transaction is a separate block, this can improve compatibility with existing tools and applications already adapted to work with blocks.

- Fast Finality: In traditional blockchains, transaction confirmation can take some time, as it needs to be included in a block and then that block confirmed by the network. If each transaction is a separate block, this could speed up the transaction confirmation process on the second layer (L2).

- Simplified Transaction Tracking: Since each transaction is a separate block, locating a specific transaction in the blockchain might be easier, as it eliminates the need to scan through multiple transactions inside one block.

This reflects a unique approach to transaction processing in the zkEVM network, which can provide high performance and convenience for users.

Thus, this design strategy not only improves RPC and P2P communication between nodes but also enhances compatibility with existing tools and ensures fast finality at the L2 level.

Transaction Execution and Trusted StateThe Trusted Sequencer reads transactions from the pool and decides whether to discard them or to order and execute them. Executed transactions are added to a transaction batch (batches), and the local L2 state of the sequencer is updated.

As previously discussed, once a transaction is added to the L2 state, it is transmitted to all other zkEVM nodes via the broadcasting service. It should be noted that relying on the Trusted Sequencer, we can achieve rapid transaction finality (faster than on L1). However, the obtained L2 state remains in a trusted (Trusted) state until the batch is recorded in the consensus contract.

Users typically interact with the trusted L2 state. However, due to certain protocol characteristics, the process of verifying L2 transactions (to enable funds withdrawal to L1) can take a long time, usually about 30 minutes, but in rare cases up to a week.

What are these rare cases?

Rare Case

- Verification of transactions on L1 will take 1 week only if the Emergency State is activated or if the aggregator does not package any proofs at all.

- Moreover, the emergency mode is activated if the sequenced batch is not aggregated (not processed by the aggregator) within 7 days. More details about the Emergency State can be viewed here.

As a result, users should be cautious about potential risks associated with high-value transactions, especially those that are irreversible, such as fund withdrawals, OTC transactions, and alternative bridges.

Batch Sequencing and Virtual StateTransaction batches now need to be ordered and verified before they can become part of the virtual (Virtual) state of L2.

Ordering Batches

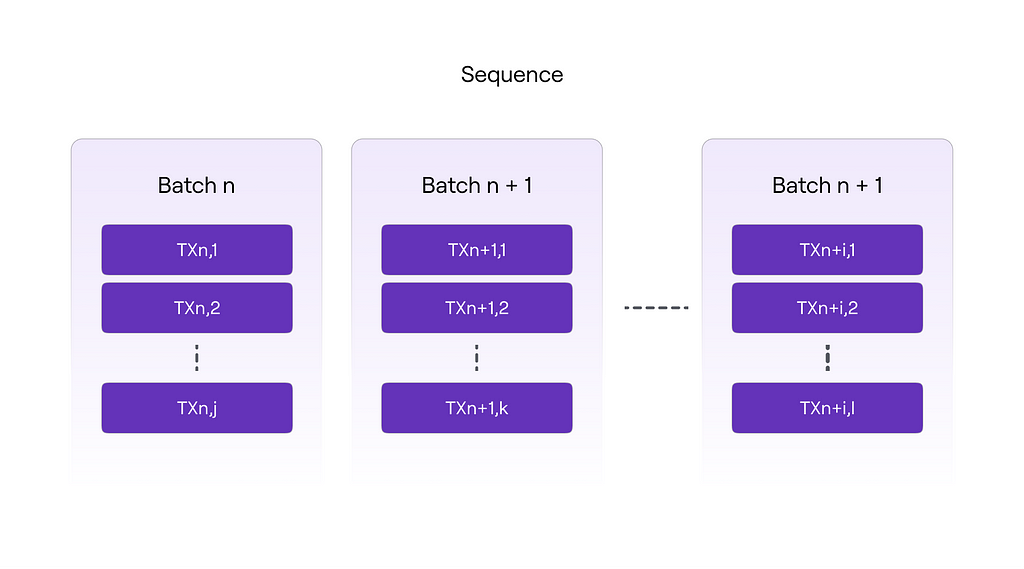

The Trusted Sequencer adds a batch of transactions to the sequence of batches through the sequenceBatches function of the PolygonZkEVM.sol (L1) contract.

The image below shows the logical structure of the batch sequence.

Thus, batch sequencing (ordering) occurs, and a new virtual state is established, which is then transmitted to L2 nodes.

It’s important to understand that there is a maximum and minimum size for a transaction batch:

- The open contract constant MAX TRANSACTIONS BYTE LENGTH defines the maximum number of transactions that can be included in a batch (300,000).

- The number of batches in a sequence (batches for one sequencing) is limited by the public contract constant MAX VERIFY BATCHES (1000). The array of batches must contain at least one batch, but not more than the value of the MAX VERIFY BATCHES constant.

It is crucial to understand what these actions entail:

- Batch Validity: This denotes the process of verifying and certifying that each data batch processed or transmitted in the L2 network is legitimate and meets established criteria and protocols. This includes verifying the correctness of transactions in the batch, their sequence, and their authenticity and protocol compliance.

- L2 State Integrity: This aspect involves maintaining and protecting the accurate and continuous state of the second layer network. State integrity ensures that all records and changes in the L2 network reflect valid transactions and interactions, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of data in the blockchain.

This verification occurs when the sequenceBatches function of the PolygonZkEVM.sol (L1) contract is called. The function iterates through each batch in the sequence and verifies its validity.

A valid batch must meet the following criteria:

- It must include a globalExitRoot value. The globalExitRoot is a unique identifier aggregating proofs of L2 transactions, allowing their secure verification and application on L1. A batch is valid only if it includes a valid globalExitRoot.

- The byte array length of transactions must be less than the MAX_TRANSACTIONS_BYTE_LENGTH constant value.

- The batch timestamp must be greater than or equal to the timestamp of the last sequenced batch but less than or equal to the block timestamp in which the L1 ordering transaction occurs.

If one batch is invalid, the transaction is canceled, discarding the entire sequence. Otherwise, if all batches subject to sequencing are valid, the sequencing process continues.

Transactions that were part of a rejected batch are not “lost” permanently. Instead, they can be resent or included in subsequent batches for processing. In a system where data security and integrity are priorities, this approach helps prevent invalid or fraudulent transactions from being incorporated into the blockchain.

State Integrity

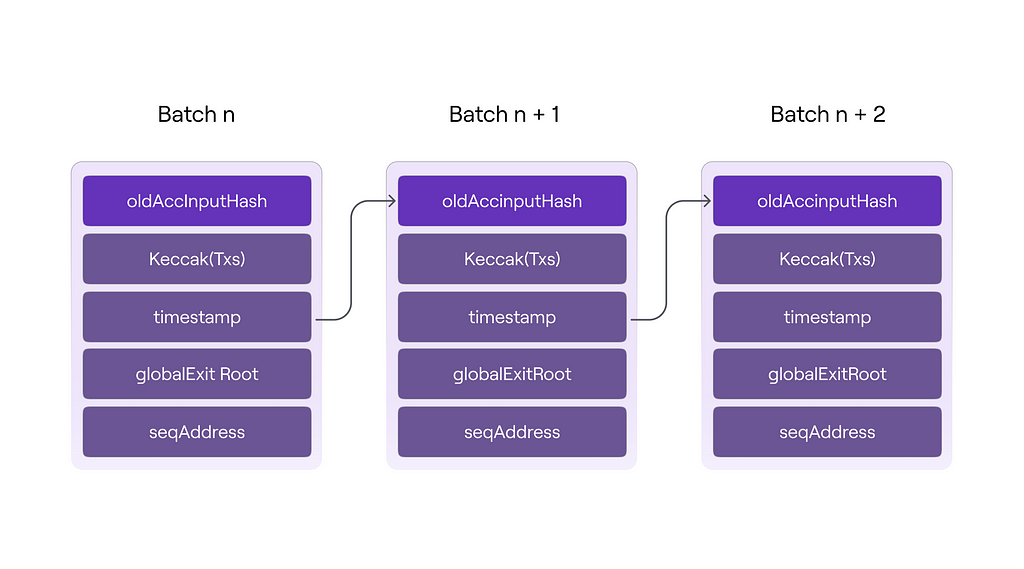

In Polygon’s zk EVM, a mechanism is used to ensure cryptographic integrity of the transaction batch chain.

Here’s how it works:

- Batch Counter: The system includes a variable called lastBatchSequenced, which acts as a batch counter. Each time a new transaction batch is formed, this counter is incremented by one. This value is used as an index number for each batch, which, in turn, serves as a positional value in the batch chain.

- Hashing Mechanism: To ensure cryptographic integrity of data between batches, a hashing mechanism similar to that used in blockchains to link blocks together is employed. This means that to compute the hash of the current batch, its data includes the hash of the previous batch.

- Accumulated Hash: The hash of a given batch represents the accumulated hash of all previous batches. This is achieved by including the hash of the previous batch (oldAccInputHash) in the computation of the current one. The accumulated hash for a specific batch is computed using the keccak256 hash function, which takes as an argument a set of data packed with abi.encodePacked.

The hash of a specific batch has the following structure:

- oldAccInputHash is the hash of the previous batch,

- keccack256(transactions) is the hash of the transaction byte array,

- globalExitRoot is the root of Bridge’s Global Exit Merkle Tree,

- timestamp is the timestamp of the batch,

- seqAddress is the address of the batch sequencer.

Thus, the hash of each batch represents the accumulated hash of all previously sequenced batches, ensuring a chain of trust and cryptographic integrity throughout the system. This approach not only guarantees data security but also facilitates verification of the chain’s integrity without the need to process each transaction individually.

Once the batches have been successfully sequenced in L1, all zkEVM nodes can synchronize their local L2 state by retrieving data directly from the L1 PolygonZkEVM.sol contract, without having to rely solely on the Trusted Sequencer. This achieves the virtual L2 state.

Batch Aggregation and Consolidated StateFinally, we move to the last part where the trusted aggregator must ultimately aggregate the sequences of batches previously transmitted by the trusted sequencer to reach the final stage of the L2 state, that is, the consolidated state.

Let’s envision the aggregator’s operation:

- The aggregator takes the sequenced batches and submits them to the Prover module;

- The Prover provides zk-proofs, confirming the integrity of the state change proposed by the sequencer;

- With the obtained zk-proofs, the aggregator goes to the L1 PolygonZkEVM.sol contract and consolidates the batch state. At this stage, the transactions are considered complete and included in the L1 state.

Within the Prover, more complex mechanisms are used to generate proofs, such as SNARK and STARK.

Using the SNARK scheme, we can ensure secure on-chain for exhaustive off-chain computations in an economical manner. For those interested, you can view an entire extensive section in the documentation explaining how the Prover module operates.

After the batches have been successfully aggregated in L1, all zkEVM nodes can verify their local L2 state by extracting and checking the consolidated roots directly from the L1 consensus contract (PolygonZkEVM.sol). As a result, the consolidated L2 state is achieved.

Resistance to MalfunctionTo ensure system resilience, participants must be rewarded for correctly performing their roles and contributing to the protocol’s finality. At present, in the early stages of the protocol, there are centralized sequencers and aggregators, but in the future, the protocol plans to decentralize them. This is why they are currently called Trusted aggregator or Trusted Sequencer.

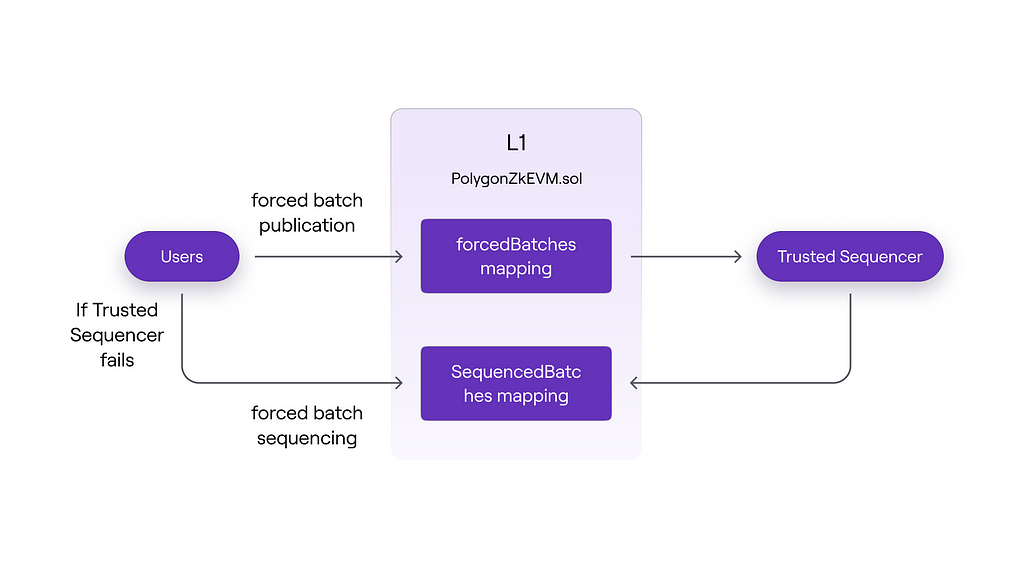

SequencerUsers must rely on the Trusted Sequencer to execute their transactions at the L2 level. However, users can include their transactions in a forced batch if they cannot execute them through the Trusted Sequencer.

In the diagram above, you can see that users can directly send transaction batches to the L1 consensus contract, where they are passed to the Trusted Sequencer and then sequenced. If for some reason users cannot execute their transactions through the sequencer, they can also send a transaction batch for sequencing to the L1 consensus contract.

It turns out that the Trusted Sequencer will include these forced batches in future sequences to maintain its trusted status. Otherwise, users can demonstrate that they are being censored, and the trust status of the Trusted Sequencer will be revoked.

AggregatorJust as the system cannot achieve L2 state finality without an active and well-functioning sequencer, finality cannot be achieved without an active and well-functioning aggregator.

The absence or failure of the Trusted Aggregator means that transitions between L2 states are never updated on L1. For this reason, the L1 PolygonZkEVM.sol contract has a verifyBatches function that allows anyone to aggregate sequences of batches.

zkEVM Emergency StateThe Emergency State is a state of the consensus contract (PolygonZkEVM.sol and PolygonZkEVMBridge.sol) that, when activated, stops batch sequencing and bridge operations.

The purpose of including an emergency state is to allow the Polygon team to address cases of malfunction or exploitation of any smart contract bugs. It is a safety measure used to protect users’ assets in zkEVM.

The following functions will be disabled in emergency mode:

- sequenceBatches

- verifyBatches

- forceBatch

- sequenceForceBatches

- proveNonDeterministicPendingState

Polygon ZK EVM represents a revolutionary approach to scaling Ethereum, allowing the use of standard Ethereum smart contract code (EVM bytecode) in a new, more efficient environment. For this, they use zkASM.

zkASM converts smart contract instructions, written in Solidity for Ethereum, into low-level code optimized for creating zk-SNARKs. This includes transforming operations and logic of smart contracts into sequences of simpler instructions.

This is similar to a translator who helps two people with different languages communicate with each other. As a result, Polygon ZK EVM allows the use of existing Ethereum smart contracts while offering the benefits of new technology, such as higher processing speeds and increased privacy.

One of the important criteria both in blockchain development and for smart contract developers themselves is the simplicity of development, testing, contract deployment, and the use of modern development tools.

Since zkEVM Polygon is based on Ethereum’s EVM, development is practically identical to development in the EVM blockchain. Popular tools such as Remix, Foundry, and Hardhat can also be used without any problems.

There are minor differences between EVM and ZkEVM:

The list includes supported EIPs, operations, and additional changes made to create zkEVM. The differences do not affect the developer experience in zkEVM compared to EVM. Gas optimization techniques, interaction with libraries like Web3.js and Ethers.js, and contract deployment work seamlessly on zkEVM without any overhead.

Opcodes

- SELFDESTRUCT → removed and replaced with SENDALL.

- EXTCODEHASH → returns the hash of the contract bytecode from the zkEVM state tree without checking whether the contract contains code.

- DIFFICULTY → returns "0" instead of a random number, as in EVM.

- BLOCKHASH → returns all previous block hashes, not just the last 256 blocks.

- NUMBER → returns the number of transactions processed.

Precompiled Contracts

The following precompiled contracts are supported in zkEVM:

- ecRecover

- identity

Other precompiled contracts do not affect the state tree of zkEVM and are processed as “revert”, returning all gas to the previous context and setting the success flag to “0”.

Thus, it should be understood that when developing a smart contract, libraries containing other precompiled contracts from this list cannot be used.

Other Minor Differences

- zkEVM does not clear storage when a contract is deployed at an address due to the specification of the zkEVM state tree. (This means that in zkEVM, when a new contract is deployed at an existing address, the data previously stored at this address is not automatically deleted. In traditional EVM, when a contract is deployed at an address where another contract already existed, the old data is deleted. However, in zkEVM, due to the specification of its state tree, this does not happen, and the old data remains in storage.)

- The JUMPDEST opcode is allowed inside push bytes to avoid bytecode analysis during execution. (This means that in zkEVM, it is allowed to use the JUMPDEST opcode within data passed by PUSH commands. In standard EVM, JUMPDEST is used to denote the place in the code where a jump (JUMP) can occur. Normally, to ensure security, bytecode is analyzed during the execution of a contract to find correct JUMPDESTs. In zkEVM, by allowing JUMPDEST to be within PUSH data, the code execution process is simplified as it does not require real-time bytecode analysis to find JUMPDEST. This speeds up contract execution and reduces their complexity.)

- zkEVM implements EIP-3541 from the London hardfork. (This means that zkEVM includes the implementation of the Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) number 3541, which was introduced to the Ethereum network during the update known as the London hardfork. EIP-3541 establishes new rules for the structure of smart contracts, prohibiting the deployment of contracts that begin with a certain byte prefix (0xEF), which prevents potential conflicts and compatibility issues with future changes in Ethereum.)

- EIP-2718, which defines a transaction type with a typed envelope, is not supported. (EIP-2718 introduces an innovation to Ethereum transaction standards by introducing a wrapper for various types of transactions. This allows multiple new transaction types to be used in the Ethereum network, each of which can have unique fields and processing logic. However, in zkEVM Polygon, as of the latest data, this standard is not supported, which means that developers and users cannot utilize the advanced features offered by typed transactions within this platform. This may affect compatibility with some new features or contracts developed for the main Ethereum network.)

- EIP-2930, which defines a transaction type with optional access lists, is not supported. (EIP-2930 is an Ethereum Improvement Proposal that introduces a new type of transaction containing optional access lists. These lists pre-specify which accounts and contract storages will be accessed by the transaction, allowing validators to know in advance which states will be affected. This improves efficiency and helps reduce gas costs by decreasing the need for redundant computations. The lack of support for EIP-2930 in zkEVM means that users and developers cannot use this functionality to optimize their transactions in the Polygon network.)

Scaling Solution

Polygon PoS primarily uses the Plasma platform and Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism to create a sidechain that operates parallel to the main Ethereum network. On the other hand, Polygon zkEVM utilizes a ZK-Rollup architecture that employs zero-knowledge proofs to provide a Layer 2 solution over Ethereum.

Consensus Mechanism

Polygon PoS relies on a set of validators who participate in the PoS consensus mechanism to verify and confirm transactions within the sidechain. Polygon zkEVM uses a consensus contract that facilitates the seamless participation of multiple coordinators (sequencers and aggregators) to create and verify batches at the L2 level.

Data Availability

In the Polygon PoS network, data is stored on a sidechain, which provides a separate blockchain system for processing transactions. Polygon zkEVM offers two modes of data availability within a hybrid scheme: Validium (data stored off-chain) and Volition (data and proofs of its correctness are on-chain for some transactions, and for others, only proofs are stored).

Smart Contract Compatibility

Polygon PoS is a sidechain that ensures compatibility with the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). This allows developers to deploy and run Ethereum smart contracts on the Polygon PoS sidechain. However, EVM compatibility implies that, despite supporting Ethereum smart contracts, there might be some differences in the execution environment. As a result, developers might need to adapt or use specific sidechain features when working with complex decentralized applications (dapps) and low-level code in Polygon PoS.

Unlike this, Polygon zkEVM is a ZK-Rollup focusing on achieving EVM equivalence. EVM equivalence implies a higher level of compatibility with Ethereum, allowing existing Ethereum smart contracts to be deployed and operated on Polygon zkEVM without any modifications. Developers do not need to change languages or tools, and they can experience a seamless transition when deploying their smart contracts on an equivalent EVM rollup. EVM equivalence effectively recreates the entire Ethereum execution environment.

The key difference is that the EVM equivalence offered by Polygon zkEVM provides “less friction” compared to the EVM compatibility offered by Polygon PoS. Polygon zkEVM is designed to ensure transparent deployment and full compatibility with Ethereum, allowing developers to maintain the same development workflow as on Ethereum, without needing any changes or reimplementation of code. In summary, Polygon zkEVM focuses on creating an almost perfect copy of the Ethereum execution environment, while Polygon PoS focuses on offering compatibility with Ethereum smart contracts in the context of a sidechain.

Security

Polygon PoS relies on its PoS validators to secure the sidechain, which operates independently of Ethereum. Polygon zkEVM inherits the security of the main Ethereum network by posting validity proofs on-chain, ensuring that off-chain computations are correct and secure.

Transaction Finality

Polygon PoS sidechains provide fast transaction finality with relatively low transaction fees. Polygon zkEVM uses zero-knowledge proofs to ensure quick off-chain transaction finality, reducing delays and fees.

Polygon PoS and Polygon zkEVM provide Layer 2 scaling solutions for Ethereum, but they differ in their architecture, consensus mechanisms, data availability parameters, and implementation details. Polygon zkEVM, in particular, uses ZK-Rollup technology to achieve improved scalability, security, and EVM equivalence while providing fast transaction finality.

Pros and Cons of zkEvm PolygonPros:- High level of security (comparable to L1);

- Smart contracts are almost fully compatible, except for some precompiled contracts;

- Contract development can use tools like Remix, Foundry, Hardhat without any problems;

- No need to set up a development stack specific to the protocol;

- Standard Web3 API (also supports standard Ethereum wallets, such as MetaMask);

- Account abstraction is supported through ERC-4337;

- Transaction processing speed — transactions on L2 are confirmed immediately and on L1 within a short period (about 30 minutes);

- Low transaction fees;

- Small size of zkSNARK on L1 to optimize user costs.

- There remains an inconvenience in contract development due to the need to check used libraries like OpenZeppelin for non-working precompiled contracts;

- Despite significant improvements in scalability, very high loads can still present a challenge;

- As a relatively new technology, it may contain unresolved issues or uncertainties.

Polygon zkEVM represents significant progress in blockchain technologies, combining Ethereum compatibility and the benefits of zero-knowledge proofs. It opens new horizons for blockchain business by offering high performance, scalability, security, and cost-efficiency. Developing for this blockchain is almost as easy as on a regular EVM blockchain. The scaling already available can help reduce the load on Ethereum and decrease users’ gas expenses. Moreover, developers are already planning to implement the EIP-4844 (Dencun) update soon, which will further reduce gas prices in the main Polygon zkEVM network in the future.

Check out our website and Telegram channel to know more about web3 development!

Links- Docs: zkEvm Polygon docs

- Video tutorials: The ULTIMATE Developers Guide To Polygon zkEVM

- Dashboard: Ecosystem

- Article: what is polygon zkEVM

- Proof of Efficiency

- The different types of ZK-EVMs

Overview of Polygon zkEVM: How the Layer 2 solution for Ethereum works was originally published in Coinmonks on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.